Athletes, coaches, and researchers agree that pain can limit endurance performance (O’Connor & Cook, 1999). Few studies have documented the verbal descriptors, i.e., symptoms, associated with moderate to intense aerobic exercise (Kinsman & Weiser, 1976; Noble & Robertson, 1996; O’Connor & Cook, 1999).

Recently, Kress & Statler (2007) have offered an operational definition of exertion pain for their article’s readers as “the intense discomfort felt when performing at sub-maximal or maximal levels.” Notice this definition in the article’s introduction used the term “discomfort”. For the study’s participants, they defined it as “the pain you feel when you are riding very hard, not the pain you feel when you have sustained an injury.” Thus they separated this component of pain from injury-related pain. Please note that they used the term pain itself rather than discomfort.

Kress & Statler studied former Olympic cyclists and ”focused specifically on how these athletes managed perceived exertion pain.” They were ”interested in how they dealt with the pain involved in the sport.” A naturalistic, grounded theory inquiry was the method of investigation they chose. Briefly, they constructed a series of ”basic questions.” The principle investigator interviewed and tape recorded all the subjects and during the last part of the session, added other probing questions. In each of the transcripts, individual “standalone” quotes were identified and added to a similar category of quotes or was used to create a new category. A total of 222 quotes were processed into 16 categories that formed lower-level themes. Of these, 12 were then integrated into 3 separate higher-order themes. Then the remaining 3 lower-level themes were promoted to be higher-level themes. With this methodology, Kress & Statler identified the following 6 higher order themes: Pain, Preparation, Mental Skills, Mind/Body, Optimism, and Control.

Pain emerged as a higher-level theme when Kress and Statler analyzed the quotes. This pain theme combined three similar yet different lower-level themes: description of pain, perception of pain, and time to termination.

The former Olympic cyclists’ personal descriptions of pain are detailed in the post, “Cyclists’ Cognitive Strategies for Coping with Pain (Part 1)”. In summary, Kress & Statler found that the cyclists “know that endurance pain exists” and that “exertion pain was out of the ordinary and unpleasant.” When the cyclists “were riding very hard”, their quotes revealed these pain descriptions: Burn Pain, Legs on Fire, Electric Shock, and Muscles are Dying. (Go to this Post)

Concerning these exertion pain descriptions, some readers of this Part 1 post may well have some unanswered questions. Well, I did! And my list of unanswered questions were these:

- Do the symptoms the cyclists reported part of their private speech, that is their self-talk? And if so, how did we learn to talk to ourselves in the first place?

- What have other studies revealed about the type of pain symptoms we experience during cycling? (Let’s remember that cognitive strategies was the focus of this study, rather than the symptoms per se.)

- Is there an effect of intensity on the symptom types reported?

- Is the processing of symptoms uni-dimensional or multi-dimensional? Does the dimensional organization of symptoms provide hints about mechanisms that provide feelings and cope with them?

- And do all persons use the same amount of detail when reporting about symptoms? If different, what impact does this have in creating miscommunication during training?

Self-Talk. This and other cyclists’ quotes also suggest that describing pain is a part of their internal conversations. Just former Olympic cyclists? Nope, all of us do! Some experts refer to our internalized narratives; others name these inner narratives only a bit differently, using terms like private speech or self-talk. I prefer to use Self-Talk. It is an ability we all develop beginning with speaking out loud to ourselves at about two to four years of age and then we shift to quiet, covert mumblings by age four or so. Early in elementary school, mumblings change to become develop silent, inner speech. In adult life, private speech may be heard during demanding activities, possibly for aiding self-regulation (see Beck, 1994).

Part of our Self-Talk might be helping us to ‘rate’ what is happening with our bodies. And when we rate our own symptoms, say about Legs are dying, then we can communicate both the descriptions and intensities of our inner body states to others. In a research article, Barrett (2004) wrote that “self-reported ratings tell us more than just how a person understands emotion-based words.” She then suggested that these results might be evidence that, “Self-report rating of emotional states are driven by the properties of the feelings that are being reported, such that people use what they know about emotion-related words to report core-affective feelings of pleasure-displeasure and felt activation.” [My emphasis added.]

As I wrote in the first post about Kress & Statler article, not only did the cyclists validate the investigators’ definition of exertion pain, they also verify words that many of us use for our own verbal descriptors of pain. Many scientists prefer only to discuss symptoms by referring to the mechanisms that may provoke them and avoid the fact that athletes ‘live’ by their feelings. “Describing how emotion experiences are caused does not substitute for a description of what is felt,” wrote Barrett (2004), “and in fact, an adequate description of what people feel is required so that scientists know what to explain in the first place” (for a review, see Barrett et al., 2007). Kress & Statler have boldly honored the cyclists by asking for descriptions of their endurance pain.

Are we athletes driven to do more than just report, or talk about, our core feelings? Yes, and I am looking forward to describing the cognitive strategies that Kress and Statler discovered when they analyzed the cyclists’ answers to the coping questions.

Other Studies. At least two other groups have found comparable results researching self-reported ratings during cycling. Cook et al. (1997) published a research article that included 4 studies investigating muscle pain during exercise. In Study #2, data was obtained for leg muscle pain using the of the long-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (LF-MPQ, Melzack, 2005). To measure pain, a word which Melzack referred to as “a single linguistic label”, he developed the LF-MPQ from 78 verbal descriptors that were then grouped into three major classes: sensory, affective, and evaluative. Cook et al. reported that the verbal descriptors “during the [incremental cycle] exercise test” were items from both the LF-MPQ Sensory and Affective classes.

The Study #4 participants used the short-form MPQ (SF-MPQ, Melzack, 1987) verbal descriptors of pain during cycle exercise. “At peak exercise most subjects … rated the pain intensity in the leg muscles as extremely intense (almost unbearable).”

Results from both studies found the most frequently reported descriptors of the MPQ Sensory class were from both LF-MPQ & SF-MPQ: Burning, Sharp, & Cramping. Additional LF-MPQ descriptors from Study #2 were Pulling & Rasping; Additional SF-MPQ descriptors from Study #4 were Heavy & Aching. From the affective class, the most frequently reported descriptors, Exhausting & Tiring, were the same when LF-MPQ or SF-MPQ was used.

Note that these participants’ report of Burning and Sharp from the Sensory class may be similar to the former Olympic cyclists’ report of Burn Pain and Electric Shock. Tiring from the Affective class may correspond to the cyclist’s report of Muscles Are Dying.

In my teens I discovered I had a talent for distance running. I really wondered how practical psychophysiological techniques could extend endurance performance. That became the single research topic that has been a focus of mine for more than 40 years. The key question was and still is, “What limits prolonged endurance?” In early 1970s, I was very fortunate to team up with Bob Kinsman, Dave Stamper, Pat Hannon, and Art Dickinson to explore how symptoms might expose the mechanisms behind the factors that limit endurance performance.

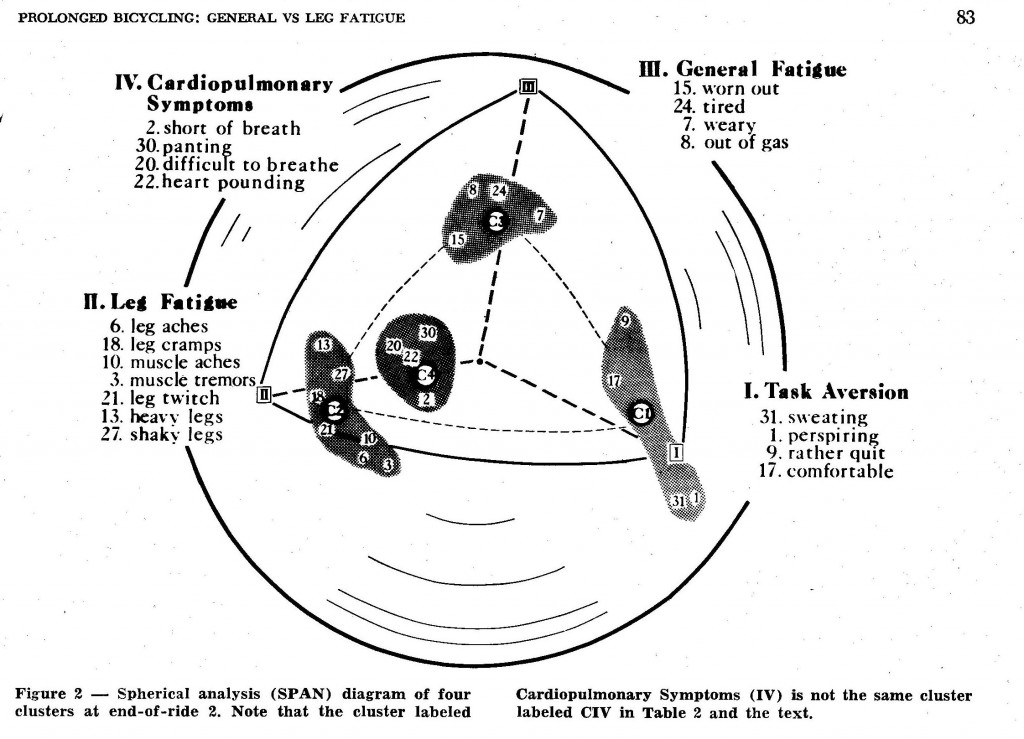

So let’s consider the following symptoms: Leg Aches, Leg Cramps, Aching Muscles, Muscle Tremors, Leg Twitching, Heavy Legs, and Shaky Legs. These symptoms had been arranged on five-point scales in a 64 item Physical Activity Questionnaire (PAQ). The participants rated the items at the end of prolonged cycling exercise at about 65% max aerobic power. Next we did a initial key-cluster factor analysis of the PAQ ( Kinsman et al., 1973), and in a subsequent key-cluster factor analysis really were able to identify the symptoms above were highly interrelated. As shown in Figure 2 from Weiser et al. (1973), the symptoms above were similar yet different from General Fatigue symptoms of Worn Out, Tired, Weary, and Out of Gas. We named this new cluster “Leg Fatigue”, and maybe a more descriptive name would have been “Leg Discomfort.”

Note that our participants’ report of Muscle Tremors and Leg Twitching might be similar to former Olympic cyclist who experienced “Electric Shock Type” pain. In addition, our participants’ report of Leg Cramps, Heavy Legs, and Shaky Legs may be similar to former Olympic cyclist who spoke about Muscles Are Dying.

Also when Cook et al. studied performance on maximal incremental cycling test, they found that leg pain was similarly described as Aching, Heavy, and Tiring-Exhausting. We studied prolonged moderate cycling and found similar descriptors: Leg Aches, Heavy Legs, and Tired

Effect of Intensity and environment. In these studies, two different exercise intensities were investigated. Kress & Statler specified in the participant’s definition of exertion pain was when the cyclists were “riding very hard.” One cyclist spoke of going “flat out.” Cook et al. collected their data after a maximal exercise test and presumably the participants’ effort was also very hard or greater. In contrast, we studied prolonged moderate sub-maximal cycling that was at a somewhat hard effort.

In our PAQ, Burning Type pain was not suggested during initial item selection and therefore was not included. My recollection was that Aching All Over was within our experiences as joggers, runners, and recreational cyclists during sustained running. Certainly, running a steep hill or doing a ‘kick’ at the end of a race is experienced by runners as a “burn.”

Regrettably, no comparison can be made to the Burn pain found in Kress & Statler’s cyclists’ narrative data. It’s interesting that that cycling locomotor recruits upper leg muscles whereas jogging & running utilize muscle of both lower and upper leg. Local metabolic changes in the upper leg muscles when “riding very hard” may be part of the Burn pain mechanism.

Another factor that might emphasize selecting Burn pain could be increased body temperature. Our studies occurred in a temperature-controlled laboratory. Sweating, Perspiring, and not Comfortable were items from our Task Aversion cluster. Were the participants feeling Hot? I definitely have had the feeling of Burning Up during the last half of long runs and races in very hot and humid conditions.

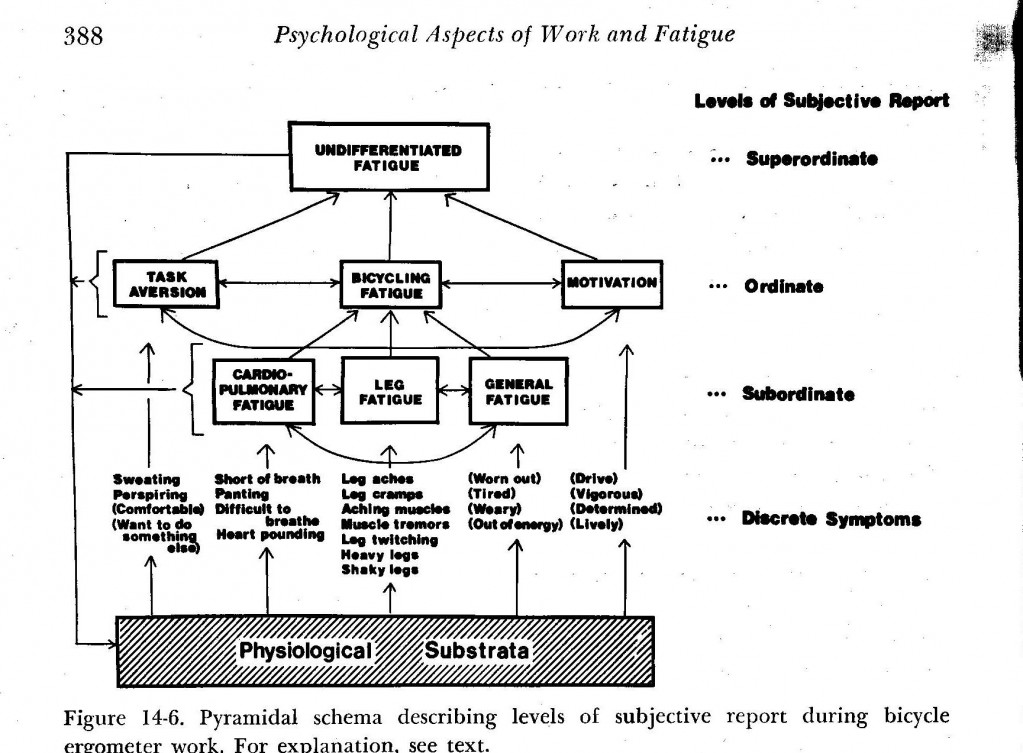

Levels of Symptom Processing. Bob Kinsman created a pyramidal schema describing the levels of bicycle exercise discomfort. He combined Leg Fatigue with the other clusters of our PAQ (Kinsman & Weiser, 1976, see Figure 14-6from reference). Four levels of subjective report ranged from many, highly differentiated Discrete Symptoms up to Undifferentiated Fatigue at the Superordinate level. Undifferentiated Fatigue was comprised of Motivation, Task Aversion, and task-specific Bicycling Fatigue input at the Ordinate level. Likewise, Bicycling Fatigue was integrated from Cardio-Pulmonary Fatigue, Leg Fatigue, and General Fatigue input at the Subordinate level. Input for each of the Ordinate and Subordinate clusters came from Discrete Symptoms.

I found it very intriguing that the MPQ sensory class verbal descriptors were very similar to the PAQ Leg Fatigue symptoms. Also the verbal descriptors MPQ affective class included symptoms from the General Fatigue clusters. Thus, these independent observations about clustering of symptoms and verbal descriptors, plus the pyramidal schema strongly suggest integrating mechanisms. These mechanisms would allow both general and specific information processing for managing bodily states during endurance performance.

Amount of Detailed Reported. Among the cyclists interviewed by Kress & Statler, please note that Ivan and Frank provided much greater depth of description than did Bill. For the curious, a greater precision in representing feeling has been termed high emotional granularity by Barrett(2004; also see Tugade, Fredrickson, & Feldman Barrett, 2004). Noticing the tendency for an athlete to be global and not so descriptive about symptoms is important for being less granular may impair the observing of details in feelings that are necessary for internal training of coping strategies. Look for more comments in the 4th blog about Granularity and how to monitor and cope with one’s symptoms.

Conclusions

- Yes, the symptoms the cyclists reported appears to be part of their self-talk. All of us have developed private speech at a young age. As adults we may use self-talk during demanding activities, possibly for aiding self-regulation. How the internal felt state for exertion pain is processed and spoken to oneself and other perhaps will become not such a mystery.

- Several studies of symptoms during cycling agree that participants report sensory-oriented verbal descriptors of heavy and aching as well as affective-oriented symptom of tiring-exhausting.

- The intensity of cycling in the Kress & Statler studies may have added the reporting of a burn verbal descriptor. Future studies of local metabolic changes in the upper leg muscles and increased body temperature when “riding very hard” may reveal part of the Burn pain mechanism.

- Is the processing of symptoms one dimensional or multi-dimensional? Thus, these independent observations about clustering of symptoms and verbal descriptors, plus the pyramidal schema strongly suggest integrating mechanisms. Again future research distinguishing processing of general versus specific information might help athletes manage bodily states during endurance performance.

- Not all persons use the same amount of detail when reporting about symptoms. Noticing the tendency for an athlete to be global and not so descriptive about symptoms is important for being less granular may impair the observing of details in feelings that are necessary for internal training of coping strategies.

Look for more comments in future posts about how symptoms are generated and the role of individual differences in Granularity to help up learn how to monitor and cope with our symptoms that limit our endurance performance.

References

Barrett, L. F. (2004) Feelings or words? Understanding the content in self-report ratings of experienced emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 266-281.

Barrett, L. F., Mesquita, B., Ochsner, K. N., & Gross, J. J. (2007) The experience of emotion. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 373-403.

Beck, L. E. (1994) Why children talk to themselves. Scientific American, 27, 78-83.

Cook, D.B., O’Connor, P.J., Eubanks, S. A., Smith, J. C., & Lee, M. (1997) Naturally occurring muscle pain during exercise: assessment and experimental evidence. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 29, 999-1012.

Kinsman, R. A., Weiser, P. C., & Stamper, D. A. (1973) Multidimensional analysis of subjective symptomatology during prolonged strenuous exercise. Ergonomics, l6, 221-226.

Kinsman, R. A., & Weiser, P. C. (1976) Subjective symptomatology during work and fatigue. In E. Simonson & P. C. Weiser (Eds.), Psychological aspects and physiological correlates of work and fatigue. Springfield, IL: Thomas, Pp. 336-405.

Kress, J. L. & Statler, T. (2007) A naturalistic investigation of former Olympic cyclists’ cognitive strategies for coping with exertional pain during performance. Journal of Sport Behavior, 30,428-452.

Melzack, R. & Torgerson, W. S. (1971) On the language of pain. Anesthesiology, 34, 50-59.

Melzack, R. (1987) The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain, 30, 191-197.

Noble B. J., & Robertson R. J. (1996) Perceived Exertion. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

O’Connor, P.J., & D.B. Cook (1999). Exercise and pain: The neurobiology, measurement, and laboratory study of pain in relation to exercise in humans. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. J.O. Holloszy & D.R. Seals (Eds.), Vol. 27, Williams & Wilkins, Pp. 119-166.

Tugade, M. M., Fredrickson, B. L., & Barrett, L. F. (2004) Psychological resilience and positive emotional granularity: Examining the benefits of positive emotions on coping and health. Journal of Personality, 72, 1161-1190

Weiser, P. C., Kinsman, R. A., & Stamper, D. A. (1973) Task-Specific symptomatology changes resulting from prolonged submaximal bicycle riding. Medicine and Science of Sports, 5, 79-85.